|

II

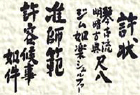

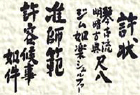

At the very start, the challenge for the student is simply to be able to play the notes. First lessons are more often than not frustrating affairs for the students who blow a lot of air through their bamboo tubes, but for all their effort, make very little sound. In the Kinko Ryu (school) in which Jim was trained, the format is quite simple: at each lesson, teacher and student kneel back on their heels, Japanese style, facing each other, with the music (in Japanese notation) between them. The teacher leads the student through each new piece, first singing the notes and counting the beat, and then they play it together. The curriculum consists of a set series of pieces that progress from simple to quite difficult. Most commonly, several sessions are spent on each piece. When the student has progressed through the entire series, the student and teacher reverse roles and start again at the beginning with the student now leading each lesson. This time, when they reach the end of the series, the first and most clearly defined stage is complete. The student may now be awarded the Jun-shi-han license although this is certainly not inevitable. Along with the license, the teacher gives a name which reflects this new rank. Jim's name, Nyoraku, means "like the essence of music."

Jim says of this accomplishment, "In order to get the Jun-shi-han license you really have to do a lot of work. That is the real nuts and bolts of being a shakuhachi player: learning all that music, turning it upside-down and teaching it to the teacher; knowing in each piece what the new challenge might be for a student; playing a recital, and then getting a certificate which says you're licensed for teaching."

Students who have the ability, time, and determination can complete this work in about five years, though Jim moved through it more slowly and received his teaching licence from Ronnie Nyogetsu Selden after twelve years. Five years later, he followed that with the next higher license, that of Shi-han, or full Master.

Students who have the ability, time, and determination can complete this work in about five years, though Jim moved through it more slowly and received his teaching licence from Ronnie Nyogetsu Selden after twelve years. Five years later, he followed that with the next higher license, that of Shi-han, or full Master.

These higher degrees or ranks, the Shi-han, and Dai-shi-han (master and grand master) are less well defined. "The idea is that you've done something to advance shakuhachi music, primarily through teaching. Starting a dojo (school) is one big way, or doing a lot of performing, " Jim explained. However, a teacher can only award licences of lesser grades than those he holds himself. Since Ronnie Nyogetsu Selden, Jim's primary teacher, was ranked as a Dai-shi-han, he could not formally advance Jim any further. In April of 2001, Aoki Reibo, Japan's Living National Treasure in shakuhachi awarded Ronnie a Koku-an Dai-shi-han (Grand Master's license at the Kyu Dan, or ninth level), making him the first non-Japanese ever to receive this high rank. At that point Ronnie, in turn, was able to award Jim his Dai-shi-han license.

What we see worked out in this process of granting licenses, ranks, and names is the concept of lineage. Westerners tend to think of lineage as related primarily to family and ancestry. But in Eastern cultures, many forms of knowledge, both theoretical and practical, are transmitted from teacher to student in a continuous line that becomes the lineage. We are familiar with the vocabulary of Guru and Disciple in a spiritual context, but it can be startling to hear the same terms used, as they are in India for example, of a sitar teacher and his students. In other times or places, where reading and writing were not the birthright of all, the only way to learn was from direct personal instruction. And the only guarantee or mark of authenticity for a teacher was his or her lineage. In addition, a statement of lineage usually also documents that lineages' history.

So at this point in our interview, we took a brief digression into the history and lineage of shakuhachi music.

The shakuhachi in its original six-hole form was imported into Japan from China at the end of the 7th century CE. Through the 12th century it was used for court music, called gagaku, of which little is known today. From then until the 16th century, a wide range of people from one of the emperors down to mendicant monks played the shakuhachi. The number of such monks increased, and eventually, in the 17th century, they formed a religious sect that looked back to a 9th century Zen monk, Fuke, as its founder. With the support of the government, monks were allowed to beg alms through playing the shakuhachi. At this time, the physical structure of the flute changed as the heavy root sections of bamboo began to be used in its construction. This not only improved the quality of the flute's sound, it also made it a useful weapon in the hands of the wandering and otherwise unarmed monks. In the late 19th century, with the collapse of the Japanese government, the Fuke sect was dissolved, and this form of shakuhachi playing went underground. But just a few years later it re-emerged when the Myoan Society was established at the Fuke Temple, Myoan-ji, and the members of this society and their students transmitted this form of shakuhachi music to the present generation of players.

As for Jim's particular lineage, his primary teacher was Ronnie Nyogetsu Selden, with whom Jim studied for fifteen years. Ronnie, in turn, was the student of Kurahashi Yodo, founder of the Mujuan Shakuhachi School. Kurahashi Yodo was a student of Jin Nyodo, one of the most famous shakuhachi players in Japanese history and a direct descendant in the lineage of the Fuke sect.

Here, Jim went into detail about Jin Nyodo: "He studied Kinko School with Kawase Junske, and other masters. He came to feel that the music was rigid and frozen and got a little disillusioned with the regimented training. He went out and traveled throughout Japan, to all these different temples, learning and collecting pieces that were not part of the limited Kinko repertoire. He selected probably about seventy pieces that formed the basis of his repertoire. Then he taught these different styles to his students, including Kurahashi Yodo, from whom Ronnie learned them. So I learned this repertoire from Ronnie, as well as a good chunk of the classical music that we also play."

Here, Jim went into detail about Jin Nyodo: "He studied Kinko School with Kawase Junske, and other masters. He came to feel that the music was rigid and frozen and got a little disillusioned with the regimented training. He went out and traveled throughout Japan, to all these different temples, learning and collecting pieces that were not part of the limited Kinko repertoire. He selected probably about seventy pieces that formed the basis of his repertoire. Then he taught these different styles to his students, including Kurahashi Yodo, from whom Ronnie learned them. So I learned this repertoire from Ronnie, as well as a good chunk of the classical music that we also play."

In recent years Jim has worked with several other teachers.

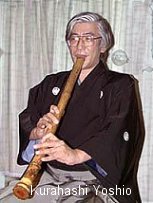

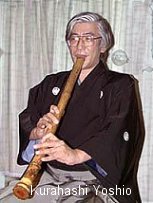

He has continued his study of traditional shakuhachi works with Kurahashi Yoshio, the son and student of Kurahashi Yodo. He has also worked with another Master of the Kinko school, Mitsuhashi Kifu, as well as with Japan's Living National Treasure in shakuhachi, Aoki Reibo, and with Taniguchi Yoshinobu.

He has continued his study of traditional shakuhachi works with Kurahashi Yoshio, the son and student of Kurahashi Yodo. He has also worked with another Master of the Kinko school, Mitsuhashi Kifu, as well as with Japan's Living National Treasure in shakuhachi, Aoki Reibo, and with Taniguchi Yoshinobu.

III

Next I asked about performing; feeling that the answer was no doubt very obvious, but something that I wanted to hear in his own words, I asked Jim if he liked performing. He was emphatic: "I love performing, I've always liked it, classical flute music, shakuhachi - it's a way of communicating my ideas and my feelings that works best for me. I like to play for that reason."

"There are really two kinds of audiences for shakuhachi: there is the kind that thinks they know what it is and they want to check it out. Generally they think, ‘Oh, Japanese, bamboo - it's going to be this mellow thing.' And they are often surprised. Traditional shakuhachi music is not particularly mellow, I don't think. It's often very dramatic and often hard to listen to - very abstract. So it's not necessarily this easy going kind of thing that people have in mind. But then there are people who know about shakuhachi and the music, so they are more involved and interested. They are more with you."

"Basically there's a kind of energy that develops when you're playing live, and the audience is responding. Sometimes they are not responding at all - that's where you really have to work hard. You have to make sure that everything you do is very clear. But at other times the group responds in a way you can read and that can really heighten a performance, heighten the energy."

"But I also always like playing when people are meditating - which happens with some regularity, such as the other night when I played at the Yoga Center: you know, thirty or so people on round cushions. That's really cool because that's what this music is for. Even though it's a step or two removed from its origin, it still has that connection. It feels quite different to play for that kind of audience. I feel much more that I am only giving, because they're only receiving. Usually audiences give back, but if someone is meditating, they're not giving back in the same way. I enjoy this very much, but it is a different kind of energy. I'm really feeding them rather than taking back from them, and I like that, in that circumstance."

IV

We went on to talk about Jim's teaching. He explained that he teaches in the traditional manner. But he does bring a lot from his western flute training to it, and this allows him to make conscious and explicit some things that the Japanese method leaves undefined. The old method involved the teacher demonstrating a piece, without much comment, and the student doing his best to imitate him. Now, however, many teachers are incorporating more verbal explanation and coaching, which makes the music more accessible to their students.

But whatever the method, teaching itself is important. Jim said, "Well, you learn a lot about your own playing and about yourself when you teach. Which is why to be a great shakuhachi player you also must be an active teacher. And they all are, all the great players are also teachers. That's the reason - because you learn so much, and it deepens your ability to play and to know music and to know yourself - teaching does that."

I asked if perhaps it didn't get repetitious, going over the same ground again and again. "No, not at all. I find it extremely challenging, and a challenge I always enjoy. Every single person that starts playing the shakuhachi has different strengths and weaknesses, and it's my job to identify, in very short order, what these are, build on the strengths and correct the weaknesses, and try to find a balance. I try to find out how to get the person to play to the best of their ability. So, yes, I find it very challenging and fun; not at all repetitious, ever."

"What's interesting is that my students come from all walks and manner of life. I have a Doctor student, a rock and roll musician student, an unemployed recent college graduate. It is interesting how people come to shakuhachi here. In Japan it may be a little different - someone's grandfather played, or they have a more direct connection to it. But here it seems people are just interested in the instrument, the sound, the music - so they start studying. I always get a thrill out of the kind of conversation you can have in lessons. And it shifts rapidly from one hour to the next. I enjoy that very much."

"Because really, how many people just want to play the shakuhachi - how much of why they study is simply to play it? I don't think that's it as often as you would think - I think there's more than that. It's a kind of a spiritual connection maybe - it's something more."

"So when you teach this music, you're teaching more. You're teaching history; you're teaching - teaching about the spirit, in a way that's not verbal or direct. And that's because it is something that has been passed on for so long. There is that weight of history (but it's a good weight!) There is a kind of connection between teacher and student that is very special and though it defies categorization in other terms, it really is more than that. It certainly is more a sense of belonging than I've ever encountered in western training. I feel a very great joy in being the most recent in a very long line of people teaching this music to other people. So I am very respectful of that position, the historical importance of that. And I try, although I'm not worthy [he laughs] - I try and live up to that. So I enjoy that feeling of passing it along, of being part of a continuity. And it's very interesting, being non-Japanese and teaching non-Japanese students."

V

Our final topic was the future. I asked where Jim would like this work to lead. "Between teaching and performing, shakuhachi takes up more and more of my time, which I'm very happy for, and between them I'm able to earn a fair amount of money each year. I would like to continue teaching, to have that continue being an important part of what I do. And I'd like a little more interaction with koto and shamisen players on a regular basis with the dojo. So instead of a students' recital once a year, I could have quarterly "Sunday afternoons" - that kind of thing."

"And then I'd love the opportunity to write, to compose more. I've written several pieces - I have ideas, and I'd love to work them through. Someday I will. I need more time - everything takes time. As for compositions, I'm not working on anything right now, but I did an interesting thing just recently - I arranged two pieces for shakuhachi and string trio (violin, viola, and cello.) That came about when some musicians asked me if I had anything we could play together. I took a traditional piece, Darani that I had just arranged for four shakuhachis and redid it for the trio. It sounds lovely - really cool. Then I took another piece, a famous koto and shakuhachi piece and arranged that too - so it was a little cross over. And that gave me the idea of writing an original piece for them, because it's a lovely sound, the three strings, and shakuhachi. So that's what I'd like to do next."

"As for shakuhachi music, more and more people are playing. More and more are interested, but interested for different reasons. I think if the music is strong enough, it will attract people. I started learning this because I liked the challenge of learning the instrument, and because I really liked the music. (I still do - I think it's really cool, special music.)" Jim said that for him, "Studying the traditional music of another culture has amplified my own cultural tradition." Moreover working with centuries old shakuhachi pieces along with new compositions, and "placing traditional and modern music side by side shows that while styles and methods change over time, feelings, emotion, and the human experience remain the same. You know, I think this music is universal, it has a universal appeal, it goes beyond being simply Japanese - it's human music."

|

In fact the idea of it being music came late in the game, as it were. There are still people, Zen Buddhists, who play only for meditation purposes. But in the 18th century,

Kurosawa Kinko,

the founder of the Kinko school, the school that I belong to, was commissioned by the guild of monk / shakuhachi players to go out and collect pieces from all over Japan and bring them back so they could be codified. It was at this point that the musical branch developed, and people began to play this material really more for entertainment than for spiritual practice. So that's where the Kinko school parted company with the rest."

In fact the idea of it being music came late in the game, as it were. There are still people, Zen Buddhists, who play only for meditation purposes. But in the 18th century,

Kurosawa Kinko,

the founder of the Kinko school, the school that I belong to, was commissioned by the guild of monk / shakuhachi players to go out and collect pieces from all over Japan and bring them back so they could be codified. It was at this point that the musical branch developed, and people began to play this material really more for entertainment than for spiritual practice. So that's where the Kinko school parted company with the rest."

During the seminar Soullberger mentioned the shakuhachi frequently - in fact he owned one, which he allowed Jim to try. "I messed around, was able to play a few sounds, and decided I needed to learn more about this." Now looking for a teacher, Jim went to a Queens College professor, Henry Burnett, with whom he had taken a course in Japanese Music. Burnett was a close friend of Ronnie Selden, one of the first westerners to master the Shakuhachi and to receive authorization to teach.

Burnett provided Jim with an introduction to Ronnie, and with that introduction, Jim began traditional training in the shakuhachi.

During the seminar Soullberger mentioned the shakuhachi frequently - in fact he owned one, which he allowed Jim to try. "I messed around, was able to play a few sounds, and decided I needed to learn more about this." Now looking for a teacher, Jim went to a Queens College professor, Henry Burnett, with whom he had taken a course in Japanese Music. Burnett was a close friend of Ronnie Selden, one of the first westerners to master the Shakuhachi and to receive authorization to teach.

Burnett provided Jim with an introduction to Ronnie, and with that introduction, Jim began traditional training in the shakuhachi.

Students who have the ability, time, and determination can complete this work in about five years, though Jim moved through it more slowly and received his teaching licence from Ronnie Nyogetsu Selden after twelve years. Five years later, he followed that with the next higher license, that of Shi-han, or full Master.

Students who have the ability, time, and determination can complete this work in about five years, though Jim moved through it more slowly and received his teaching licence from Ronnie Nyogetsu Selden after twelve years. Five years later, he followed that with the next higher license, that of Shi-han, or full Master.

Here, Jim went into detail about Jin Nyodo: "He studied Kinko School with Kawase Junske, and other masters. He came to feel that the music was rigid and frozen and got a little disillusioned with the regimented training. He went out and traveled throughout Japan, to all these different temples, learning and collecting pieces that were not part of the limited Kinko repertoire. He selected probably about seventy pieces that formed the basis of his repertoire. Then he taught these different styles to his students, including Kurahashi Yodo, from whom Ronnie learned them. So I learned this repertoire from Ronnie, as well as a good chunk of the classical music that we also play."

Here, Jim went into detail about Jin Nyodo: "He studied Kinko School with Kawase Junske, and other masters. He came to feel that the music was rigid and frozen and got a little disillusioned with the regimented training. He went out and traveled throughout Japan, to all these different temples, learning and collecting pieces that were not part of the limited Kinko repertoire. He selected probably about seventy pieces that formed the basis of his repertoire. Then he taught these different styles to his students, including Kurahashi Yodo, from whom Ronnie learned them. So I learned this repertoire from Ronnie, as well as a good chunk of the classical music that we also play."

He has continued his study of traditional shakuhachi works with Kurahashi Yoshio, the son and student of Kurahashi Yodo. He has also worked with another Master of the Kinko school, Mitsuhashi Kifu, as well as with Japan's Living National Treasure in shakuhachi, Aoki Reibo, and with Taniguchi Yoshinobu.

He has continued his study of traditional shakuhachi works with Kurahashi Yoshio, the son and student of Kurahashi Yodo. He has also worked with another Master of the Kinko school, Mitsuhashi Kifu, as well as with Japan's Living National Treasure in shakuhachi, Aoki Reibo, and with Taniguchi Yoshinobu.